CCPA Rulemaking - Cybersecurity Audits

II. Comments On Proposed Rulemaking For Cybersecurity Audits, Risk Assessments, and Automated Decisionmaking

III. Appendix A - Current Process for Mandatory Independent Security Assessments of California Agencies

IV. Appendix B - California State Legislation related to Cybersecurity, Consumer Privacy Protections, and Public Safety

V. Appendix C - Proposed Control Set for Initial Risk Assessment Summaries for Identifying High-risk Entities

On February 4, 2023, the CPPA requested public comments on three items approved by voters in the ballot measure, Prop. 24, for further consideration in finalizing the Regulations:

- cybersecurity audits

- risk assessments

- automated decisionmaking

In public comments I submitted to the CPPA on March 27, 2023, I referenced CCPA compliance test cases that can be evaluated using NIST SP 800-53r5 control standards:

- Consistency with Consumers' reasonable expectations

- Consumers' control over their personal information

- Consumers' ability to knowingly and freely negotiate with a business over the business’s use of their personal information

The public comments I submitted, and three appendices, are published here

and can also be accessed from my public data catalog and code repository.

-

PrivacyPortfolio's public Github repository

-

PrivacyPortfolio's public data catalog on data.world:

COMMENTS ON PROPOSED CCPA RULEMAKING.docx

Appendix A - Current Process for Mandatory Independent Security Assessments of California Agencies.docx

Appendix B - California State Legislation related to Cybersecurity, Consumer Privacy Protections, and Public Safety.docx

Appendix C - Proposed Control Set for Initial Risk Assessment Summaries for Identifying High-risk Entities.docx

Appendix C - NIST Control Standards for CCPA Risk Assessments.xlsx

Commenter: Craig Erickson, a California Consumer residing in Alameda, CA

Contact: craig-erickson@privacyportfolio.com

Date Submitted: 03/27/2023

Craig Erickson’s Comments On Proposed Rulemaking For

Cybersecurity Audits, Risk Assessments, and Automated Decisionmaking

Background

As a California

Consumer, I maintain a personal vendor risk program for testing

businesses’ compliance with the CCPA

and governing use of my

personal information.

I voted for Proposition

24, the California Privacy Rights Act of 2020 (“CPRA”) because I share

“the goal of restricting or prohibiting the processing

if the risks to privacy of the consumer outweigh the benefits

resulting from

processing to the consumer, the business, other stakeholders, and the

public”.

Comment 1, Pursuant to Civil Code section 1798.185(a)(15)-(16):

(15) Issu[e] regulations requiring businesses whose processing of consumers’ personal information presents significant risk to consumers’ privacy or security, to: (A) Perform a cybersecurity audit on an annual basis, including defining the scope of the audit and establishing a process to ensure that audits are thorough and independent. The factors to be considered in determining when processing may result in significant risk to the security of personal information shall include the size and complexity of the business and the nature and scope of processing activities.

(B) Submit to the California Privacy Protection Agency on a regular basis a risk assessment with respect to their processing of personal information, including whether the processing involves sensitive personal information, and identifying and weighing the benefits resulting from the processing to the business, the consumer, other stakeholders, and the public, against the potential risks to the rights of the consumer associated with that processing, with the goal of restricting or prohibiting the processing if the risks to privacy of the consumer outweigh the benefits resulting from processing to the consumer, the business, other stakeholders, and the public. Nothing in this section shall require a business to divulge trade secrets.

I ask the Agency to

consider all stakeholders when issuing regulations 1798.185(a)(15)-(16).

Consumers and government

agencies can also introduce significant risk by their actions or

inaction

even though they cannot

be legally responsible for following the guidance issued by these

regulations.

In addition to requiring

businesses to perform risk assessments and cybersecurity audits:

(B) Consumers should be

allowed to submit to the California Privacy Protection Agency on an

as-needed basis,

their own risk

assessment findings, compliance test results, or incident reports with

respect to their processing of personal information,

and that the Agency

should help identify and weigh the benefits against potential risks,

with the goal of

educating the public about which processing activities and

organizational entities are deemed “high-risk”.

and

(A) Based on risk

assessments (B) from businesses and consumers which are validated by the

Agency,

perform a cybersecurity

audit on an annual basis using the State of California’s current process

as a model

to ensure that audits

are thorough and independent.

This proposal is documented in

Appendix A

.

(a) The non-exclusive

factors to be considered in determining when processing may result in

significant risk

to the security of

personal information shall include any one of the following factors:

- the size of the business;

- complexity of supply-chain dependencies;

- the nature of processing activities;

- scope in terms of company size;

- sensitivity of personal information;

- vulnerability of targeted populations;

- history of non-compliance, breaches, or unlawful practices;

- absence of, or lack of access to other suppliers providing critical services to consumers.

(16) Issu[e] regulations governing access and opt-out rights with respect to businesses’ use of automated decisionmaking technology, including profiling and requiring businesses’ response to access requests to include meaningful information about the logic involved in those decisionmaking processes, as well as a description of the likely outcome of the process with respect to the consumer.

(16) Consider issuing

regulations governing access and opt-out rights with respect to any, and

all use of automated decisionmaking technology.

Businesses aren’t the

only entities using automated decisionmaking technologies;

government agencies use

it in law enforcement,

and consumers use it

when transmitting opt-out preference signals

or when using authorized

agents to send delete requests to businesses identified in email

messages.

Comment 2, I. Cybersecurity Audits; Question 1 (a) (b) (c) (d) (e):

In determining the necessary scope and process for these audits, the Agency is interested in learning more about existing state, federal, and international laws applicable to some or all CCPA-covered businesses or organizations that presently require some form of cybersecurity audit related to the entity’s processing of consumers’ personal information; other cybersecurity audits, assessments, or evaluations that are currently performed, and cybersecurity best practices; and businesses’ relevant compliance processes. Accordingly, the Agency asks: 1. What laws that currently apply to businesses or organizations (individually or as members of specific sectors) processing consumers’ personal information require cybersecurity audits? For the laws identified: a. To what degree are these laws’ cybersecurity audit requirements aligned with the processes and goals articulated in Civil Code section 1798.185(a)(15)(A)?

1.a.

California already has

an established Cybersecurity Program including Independent Security

Audits for its agencies,

which appears to meet

the goals and requirements of Civil Code section 1798.185(a)(15)(A)

with minimal

modifications, as these state agencies serve both businesses and

consumers.

California State Laws

and the California State Constitution require California State Agencies

to have mandatory cybersecurity audits,

and in some cases,

Privacy Impact Assessments.

b. What processes have businesses or organizations implemented to comply with these laws that could also assist with their compliance with CCPA’s cybersecurity audit requirements?

1.b. California’s ISA process, documented in

Appendix A

, helps agencies

comply with other state laws that currently have,

or could benefit from,

cybersecurity audit requirements.

These laws, which are

related to security and privacy risks of processing personal

information,

could be more effective

by sharing information and costs from CCPA-mandated risk assessments and

cybersecurity audits.

These current and pending legislative bills are documented in

Appendix B

.

c. What gaps or weaknesses exist in these laws for cybersecurity audits? What is the impact of these gaps or weaknesses on consumers? d. What gaps or weaknesses exist in businesses’ compliance processes with these laws for cybersecurity audits? What is the impact of these gaps or weaknesses on consumers?

1.c. and 1.d. The gaps

or weaknesses of any audit or certification is the level of acceptance

or validation of the assessment.

Obviously, Californians

would not vote for mandatory risk assessments and cybersecurity audits

if existing ones met the

goals and requirements of laws like Civil Code section

1798.185(a)(15)(A).

The lack of transparency

about which standards and controls are tested, what the process is,

the desired outcomes,

and who this information applies to,

all factor into

consumers’ trust in businesses and enforcement agencies.

Laws are ineffective

when perceived by businesses or consumers as being unfairly enforced.

e. Would you recommend that the Agency consider the cybersecurity audit models created by these laws when drafting its regulations? Why, or why not?

1.e. I recommend using a similar model to the existing ISA process within the State because the CPPA is a state agency, and the State uses NIST SP800-53r4 as its primary standard control framework, according to the Office of Information Security (OIS) in the State’s Information Security Policy.

Comment 3, I. Cybersecurity Audits; Question 2 (a) (b) (c) (d) (e):

2. In addition to any legally-required cybersecurity audits identified in response to question 1, what other cybersecurity audits, assessments, or evaluations that are currently performed, or best practices, should the Agency consider in its regulations for CCPA’s cybersecurity audits pursuant to Civ. Code § 1798.185(a)(15)(A)? For the cybersecurity audits, assessments, evaluations, or best practices identified: a. To what degree are these cybersecurity audits, assessments, evaluations, or best practices aligned with the processes and goals articulated in Civil Code § 1798.185(a)(15)(A)?

2.a. The Agency should consider in its regulations for CCPA’s cybersecurity audits pursuant to Civ. Code § 1798.185(a)(15)(A) alignment with cybersecurity audits, assessments, evaluations, and best practices identified in intra-state, inter-state, and federal requirements and standards, and standards from the EU including the GDPR, the EDPB, and NIS 2.

b. What processes have businesses or organizations implemented to complete or comply with these cybersecurity audits, assessments, evaluations, or best practices that could also assist with compliance with CCPA’s cybersecurity audit requirements? c. What gaps or weaknesses exist in these cybersecurity audits, assessments, evaluations, or best practices? What is the impact of these gaps or weaknesses on consumers? d. What gaps or weaknesses exist in businesses or organizations’ completion of or compliance processes with these cybersecurity audits, assessments, evaluations, or best practices? What is the impact of these gaps or weaknesses on consumers?

2.b., 2.c. and 2.d.

Current cybersecurity audits, assessments, evaluations, or best

practices in the US

include responding to

self-assessment questionnaires from other businesses,

and third-party

certifications such as SOC2, PCI-DSS, HITRUST, FedRAMP, and ISO.

Consumers do not have

access to this information, which is both a gap and a weakness which

impacts consumers and businesses

by eroding public trust

that laws are being fairly and effectively enforced.

Comment 4, I. Cybersecurity Audits; Question 2 (e), and Question 3:

2.e. Would you recommend that the Agency consider these cybersecurity audit models, assessments, evaluations, or best practices when drafting its regulations? Why, or why not? If so, how? 3. What would the benefits and drawbacks be for businesses and consumers if the Agency accepted cybersecurity audits that the business completed to comply with the laws identified in question 1, or if the Agency accepted any of the other cybersecurity audits, assessments, or evaluations identified in question 2? How would businesses demonstrate to the Agency that such cybersecurity audits, assessments, or evaluations comply with CCPA’s cybersecurity audit requirements?

2. e. The Agency should

consider these cybersecurity audit models, assessments, evaluations, or

best practices

when drafting its

regulations because, when aligned with common controls in other standard

control frameworks,

the compliance and audit

process can facilitate greater acceptance and leverage information from

existing best practices.

However, due to the wide

variety of interpretations and inconsistent audit execution in these

other models,

existing assessments

should not be accepted in place of a state agency-initiated audit

that sets the control

standards and the audit methodology.

Comment 5, I. Cybersecurity Audits; Question 4, and Question 5:

4. With respect to the laws, cybersecurity audits, assessments, or evaluations identified in response to questions 1 and/or 2, what processes help to ensure that these audits, assessments, or evaluations are thorough and independent? What else should the Agency consider to ensure that cybersecurity audits will be thorough and independent? 5. What else should the Agency consider to define the scope of cybersecurity audits?

Questions 4. and 5.

Similar processes from other government agencies help to ensure that

these audits, assessments, or evaluations

are thorough and

independent, by comparing existing cases which are also relevant to the

CCPA.

The Agency should

consider publishing a “Communicating our Regulatory and Enforcement

Activity Policy”,

as the ICO does in the

UK because:

Transparency is often

mentioned as a key factor in building and maintaining trust among

businesses and consumers.

Transparency is also a

preventative control mechanism – when businesses and consumers know what

enforcement actions are taken,

why, and on whom can

invoke a sense of fairness, which research has shown tends to encourage

compliance.

This topic about

transparency relates directly to the Agency’s question regarding the

scope of cybersecurity audits:

The scope should be

dependent upon the classification of business practices and business

entities

whose management history

has been deemed “high-risk” and should not be concealed from the

public.

For example, the Agency

should also consider “trust services” (NIS 2) that are essential to

identity verification,

or data brokers that

operate CDNs or other services that must be resilient for serving the

public interest.

Article 2 of The Network

and Information Security (NIS 2) Directive, the EU-wide legislation on

cybersecurity states:

“2. Regardless of their size, this Directive also applies to entities … where:

-

services are provided by:

(i) providers of public electronic communications networks or of publicly available electronic communications services;

(ii) trust service providers;

(iii) top-level domain name registries and domain name system service providers; - the entity is the sole provider in a Member State of a service which is essential for the maintenance of critical societal or economic activities;

- disruption of the service provided by the entity could have a significant impact on public safety, public security or public health;

- disruption of the service provided by the entity could induce a significant systemic risk, in particular for sectors where such disruption could have a cross-border impact;

- the entity is critical because of its specific importance at national or regional level for the particular sector or type of service, or for other interdependent sectors in the Member State;”

Comment 6, II. Risk Assessments; Question 1 (a), and Question 5:

In determining the necessary scope and submission process for these risk assessments, the Agency is interested in learning more about existing state, federal, and international laws, other requirements, and best practices applicable to some or all CCPA-covered businesses or organizations that presently require some form risk assessment related to the entity’s processing of consumers’ personal information, as well as businesses’ compliance processes with these laws, requirements, and best practices. In addition, the Agency is interested in the public’s recommendations regarding the content and submission-format of risk assessments to the Agency, and compliance considerations for risk assessments for businesses that make less than $25 million in annual gross revenue. Accordingly, the Agency asks: 1. What laws or other requirements that currently apply to businesses or organizations (individually or as members of specific sectors) processing consumers’ personal information require risk assessments? For the laws or other requirements identified: a. To what degree are these risk-assessment requirements aligned with the processes and goals articulated in Civil Code § 1798.185(a)(15)(B)? 5. What would the benefits and drawbacks be for businesses and consumers if the Agency accepted businesses’ submission of risk assessments that were completed in compliance with GDPR’s or the Colorado Privacy Act’s requirements for these assessments? How would businesses demonstrate to the Agency that these assessments comply with CCPA’s requirements?

1.a. The risk assessment

itself should determine the necessary scope and submission process

for selecting which

businesses should be subject to mandated cybersecurity audits.

Existing state, federal,

and international laws, third-party compliance audits employ a similar

approach

by using self-assessment

questionnaires and other tools to evaluate an entity’s legal

requirements

and then determine if

the inherent risk justifies additional scrutiny or controls --

even for businesses that

make less than $25 million in annual gross revenue or enjoy other

exemptions.

Comment 7, Pursuant to II. Risk Assessments; Question 1 (b) (c) (d) and (e):

b. What processes have businesses or organizations implemented to comply with these laws, other requirements, or best practices that could also assist with compliance with CCPA’s risk-assessments requirements (e.g., product reviews)?

Businesses evaluate other businesses through vendor risk management practices,

including the use of

“ratings” companies and databases such as MITRE’s CVE and US-CERT,

to identify product

vulnerabilities and data breach histories which can also assist with the

CCPA’s risk-assessments requirements.

c. What gaps or weaknesses exist in these laws, other requirements, or best practices for risk assessments? What is the impact of these gaps or weaknesses on consumers? d. What gaps or weaknesses exist in businesses’ or organizations’ compliance processes with these laws, other requirements, or best practices for risk assessments? What is the impact of these gaps or weaknesses on consumers?

The gaps or weaknesses of existing risk assessments include:

lack of data quality standards in reporting

and the lack of

participation in sharing information about security and privacy

incidents among businesses, consumers, and enforcement agencies.

These weaknesses impact

consumers by depriving them of critical information they need to make

risk-based decisions about their vendors.

Not-for-profit

Organizations, with few exceptions, are currently exempt from complying

with the CCPA.

According to page 2 of

“Findings from ICO information risk reviews at eight charities”, April

2018,

charitable organizations

can be large or small, and engage in very high-risk processing.

Under the section

entitled, “Typical processing of personal data by charities”, the ICO

writes,

“The charities

involved process a limited amount of sensitive personal data as defined

by the DPA,

including staff

sickness records and sometimes donor or service user information

relating to health

and receipt of

benefits. Some charities also process information relating to children

and vulnerable people.”

e. Would you recommend the Agency consider the risk assessment models created through these laws, requirements, or best practices when drafting its regulations? Why, or why not? If so, how?

This is why I propose the Agency send a risk assessment to every organization registered with the California Secretary of State, not only for the purpose of determining inherent risk but also for increasing the public’s awareness of these new regulations and the standards used in these assessments.

Comment 8, Pursuant to II. Risk Assessments; Question 2:

2. What harms, if any, are particular individuals or communities likely to experience from a business’s processing of personal information? What processing of personal information is likely to be harmful to these individuals or communities, and why?

I cannot predict what

harms, if any, particular individuals or communities are likely to

experience

from a business’s

processing of personal information.

Identifying what

processing of personal information is likely to be harmful to these

individuals or communities,

could be discovered

through robust reporting process,

which would accept input

from individual consumers and/or consumer advocacy organizations such

as the Identity Theft Resource Center.

I recommend not

codifying in law or regulations assumptions or current trends which may

not hold true in the future,

in favor of capturing

incident-reporting metrics instead.

Comment 6, Pursuant to II. Risk Assessments; Question 3 (a):

3. To determine what processing of personal information presents significant risk to consumers’ privacy or security under Civil Code § 1798.185(a)(15): a. What would the benefits and drawbacks be of the Agency following the approach outlined in the European Data Protection Board’s Guidelines on Data Protection Impact Assessment?

3.a. To determine what processing of personal information presents significant risk to consumers’ privacy or security under Civil Code § 1798.185(a)(15), the Agency should follow an approach similar to those outlined in the European Data Protection Board’s Guidelines on Data Protection Impact Assessment.

Comment 9, Pursuant to II. Risk Assessments; Question 3 (b) (c) and (d):

b. What other models or factors should the Agency consider? Why? How? c. Should the models or factors be different, or assessed differently, for determining when processing requires a risk assessment versus a cybersecurity audit? Why, or why not? If so, how? d. What processing, if any, does not present significant risk to consumers’ privacy or security? Why?

3.b.c.d. The agency

should consider the PIA Methodology from CNIL for Privacy Impact

Assessments

because of its

widespread adoption and online tools for conducting them.

The Agency should also

consider the ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 27/WG 5 N1320, WG 5 Standing Document 4

(SD4) – Standards Privacy Assessment (SPA).

This document determines

whether to apply the SPA process by asking three questions concerning

the Standard or Specification Under Review (SUR):

- Will the SUR involve technology that will process PII, or will it involve technology that could link information to an identifiable individual?

- If the SUR will not process PII or involve technology that could link information to an identifiable individual, will it generate PII?

- If the SUR will not generate PII, will it involve technology that will be used in a network device by an individual?

If the answer to any of

these questions is affirmative, then the SPA process should be applied

to the SUR

because of the

likelihood that processing does involve significant risk.

The beauty of this

approach lies in its granularity, as applied to an entire product

offering or introducing a new feature,

rather than applying it

to an entire enterprise.

Otherwise, in response

to Question 3.d, processing does not present significant risk when:

“This standard [or

specification] does not define technology that will process Personally

Identifiable Information (PII),

nor will it create

any link to PII.

Furthermore, the

standard [or specification] does not define technology that will be

deployed in a network device and used by an individual.”

Comment 10, Pursuant to II. Risk Assessments; Question 3 (c):

c. Should the models or factors be different, or assessed differently, for determining when processing requires a risk assessment versus a cybersecurity audit? Why, or why not? If so, how?

The risk assessment

should be used initially to determine what personal information is

processed by an entity,

and what their legal

obligations are in complying with the CCPA,

so that all stakeholders

including businesses, consumers, and the Agency can judge for

themselves

if a cybersecurity audit

should be required based on the design of appropriate controls.

To protect trade secrets

and security measures, only the resulting status should be reported for

each entity

when or if the entity’s

status is queried by users through an online tool provided by the CPPA.

Comment 11, Pursuant to II. Risk Assessments; Question 4 (a) (b):

4. What minimum content should be required in businesses’ risk assessments? In addition: a. What would the benefits and drawbacks be if the Agency considered the data protection impact assessment content requirements under GDPR and the Colorado Privacy Act? b. What, if any, additional content should be included in risk assessments for processing that involves automated decisionmaking, including profiling? Why?

4. The minimum content

required in risk assessments should be based on a subset of the most

fundamental controls in NIST SP 800-53 r5

which are directly

applicable to the CCPA Regulations,

and can be mapped to

controls in other frameworks such as NIST Cybersecurity Framework, NIST

Privacy Framework,

and the NIST Framework

for Improving Critical Infrastructure, Center for Internet Security

Controls, OWASP, and ISO.

As a theoretical construct, I have proposed in

Appendix C

, a subset of

selected NIST controls

which provide acceptable

standards for cybersecurity and information risk practices that are

necessary for complying with the CCPA Regulations.

4.a The GDPR and the

Colorado Privacy Act are laws which are subject to change, making these a

poor choice for the CCPA’s risk assessments.

A better choice would be

to base risk assessments on standard, mature control frameworks like

NIST,

which is a commonly used

by state and federal government agencies and all companies that do

business with these agencies.

4.b Additional content

is not required in risk assessments for processing that involves

automated decisionmaking,

including profiling

because several controls included in my proposed NIST subset covers

underlying dependencies

like data quality and

provenance, which are marked with an asterisk in

Appendix C - NIST Control Standards for CCPA Risk Assessments.xlsx

.

Additional content may

be required for mandated cybersecurity audits according to relevant risk

factors.

Comment 12, Pursuant to II. Risk Assessments; Question 6 (a):

6. In what format should businesses submit risk assessments to the Agency? In particular: a. If businesses were required to submit a summary risk assessment to the Agency on a regular basis (as an alternative to submitting every risk assessment conducted by the business): i. What should these summaries include? ii. In what format should they be submitted? iii. How often should they be submitted?

6.a Businesses should

only submit summary risk assessments formatted as a self-assessment

questionnaire issued by the Agency,

for the purpose of

identifying risk factors ascribed to their company.

The Agency should not

accept any other risk assessment conducted by the business because most

other assessments will likely be outdated

and not aligned with

CPPA standards which are not yet defined.

These summaries should

include a relevant subset of controls based on the NIST standard,

similar to my Comment 11, which is documented in Appendix C.

They should be submitted

at least once annually, or within 90 days of a change in ownership.

Comment 13, Pursuant to II. Risk Assessments; Question 6 (b):

b. How would businesses demonstrate to the Agency that their summaries are complete and accurate reflections of their compliance with CCPA’s risk assessment requirements (e.g., summaries signed under penalty of perjury)?

6.b. Businesses should

designate a company officer that attests to the completeness, accuracy,

and currency of risk assessment summaries,

signed by the designated

officer under penalty of perjury,

like NIS 2 attestations in the EU, or Sarbanes Oxley in the US.

Combined with other

proposals I’ve made in these comments,

these summaries can be

verified or refuted by incident reporting and complaints from consumers

and other enforcement agencies.

Comment 14, Pursuant to II. Risk Assessments; Question 7:

7. Should the compliance requirements for risk assessments or cybersecurity audits be different for businesses that have less than $25 million in annual gross revenues? If so, why and how?

All organizational entities registered with the California Secretary of State should be required to submit an initial risk assessment, which consists of no more than 100 self-assessment questions designed to identity high-risk processing and high-risk entities. These self-assessment questions are provided alongside the NIST controls I mapped to CCPA Regulations in Appendix C.

Comment 15, Pursuant

to III. Automated Decisionmaking; Question 3 and Question 4:

In determining the necessary scope of such regulations, the Agency is interested in learning more about existing state, federal, and international laws, other requirements, frameworks, and/or best practices applicable to some or all CCPA-covered businesses or organizations that presently utilize any form of automated decisionmaking technology in relation to consumers, as well as businesses’ compliance processes with these laws, requirements, frameworks, and/or best practices. In addition, the Agency is interested in learning more about businesses’ uses of and consumers’ experiences with these technologies, including the prevalence of algorithmic discrimination. Lastly, the Agency is interested in the public’s recommendations regarding whether access and opt-out rights should differ based on various factors, and how to ensure that access requests provide meaningful information about the logic involved in automated decisionmaking processes as well as a description of the likely outcome of the process with respect to the consumer. Accordingly, the Agency asks: 3. With respect to the laws and other requirements, frameworks, and/or best practices identified in response to questions 1 and 2: a. How is “automated decisionmaking technology” defined? Should the Agency adopt any of these definitions? Why, or why not?

3.a. The Agency should use the ICO definition because it’s the most concise:

** NOT FOUND **

What is Automated Decision-making?

For related terms, I also recommend:

AI Watch. Defining Artificial Intelligence 2.0

which provides an

“operational definition” consisting of an iterative method providing a

concise taxonomy

and list of keywords

that characterise the core domains of the AI research field.

b. To what degree are these laws, other requirements, frameworks, or best practices aligned with the requirements, processes, and goals articulated in Civil Code § 1798.185(a)(16)?

3.b. The Agency should consider all regulatory frameworks regarding the use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) because AI is the baseline technology underlying Automated Decisionmaking technologies. In particular, the Agency should consider:

- Regulatory framework proposal on artificial intelligence | Shaping Europe’s digital future (europa.eu)

- explaining-decisions-made-with-artificial-intelligence-1-0.pdf from the ICO

- guidance-on-the-ai-auditing-framework-draft-for-consultation.pdf from the ICO

The Agency should also consider which AI systems the EU has identified as high-risk in its Regulatory framework proposal on artificial intelligence, for inclusion in its criteria for defining high-risk factors:

- critical infrastructures (e.g. transport), that could put the life and health of citizens at risk;

- educational or vocational training, that may determine the access to education and professional course of someone’s life (e.g. scoring of exams);

- safety components of products (e.g. AI application in robot-assisted surgery);

-

employment, management of workers and access to self-employment

(e.g. CV-sorting software for recruitment procedures); -

essential private and public services

(e.g. credit scoring denying citizens opportunity to obtain a loan); -

law enforcement that may interfere with people’s fundamental rights

(e.g. evaluation of the reliability of evidence); -

migration, asylum and border control management

(e.g. verification of authenticity of travel documents);

3.c. What processes have businesses or organizations implemented to comply with these laws, other requirements, frameworks, and/or best practices that could also assist with compliance with CCPA’s automated decisionmaking technology requirements? 4. How have businesses or organizations been using automated decisionmaking technologies, including algorithms? In what contexts are they deploying them? Please provide specific examples, studies, cases, data, or other evidence of such uses when responding to this question, if possible.

3.c. and 4. The vast

majority of businesses in the US are currently using automated

decisionmaking, machine-learning, and artificial intelligence

as marketing buzzwords

to position themselves favorably in the market.

This is problematic

because it could be nearly impossible for the Agency to determine who is

using this technology,

especially when

companies make false representations about their products and services,

or when they imply

compliance with various laws without actually doing so,

because they fall under

the CCPA revenue threshold and can avoid public embarrassment AND

regulatory scrutiny.

Businesses which are

exempt from the CCPA and are reluctant to acknowledge this in public,

can effectively defraud

consumers regarding their CCPA rights,

according to controlled

privacy experiments I have conducted over a two year period.

I anticipate that

business start-ups, who are eager to accelerate their market positions

but less eager to implement privacy controls,

will claim to use AI,

ML, Deep Neural Networks, etc.

4. Existing GDPR case

law, and associated privacy harms can be found in the following report:

Automated Decision-Making Under the GDPR:

Practical Cases from Courts and Data Protection Authorities

Comment 16, Pursuant

to III. Automated Decisionmaking; Question 3 (a) (d) (e) (f) and

Question 5:

d. What gaps or weaknesses exist in these laws, other requirements, frameworks, and/or best practices for automated decisionmaking? What is the impact of these gaps or weaknesses on consumers? e. What gaps or weaknesses exist in businesses or organizations’ compliance processes with these laws, other requirements, frameworks, and/or best practices for automated decisionmaking? What is the impact of these gaps or weaknesses on consumers? f. Would you recommend that the Agency consider these laws, other requirements, frameworks, or best practices when drafting its regulations? Why, or why not? If so, how?

3.d.e.f. I recommend the Agency analyze how its own regulations on ADM would or would not apply to use cases in the EU, in light of the other conflicting US laws which could circumvent these protections.

5. What experiences have consumers had with automated decisionmaking technology, including algorithms? What particular concerns do consumers have about their use of businesses’ automated decisionmaking technology? Please provide specific examples, studies, cases, data, or other evidence of such experiences or uses when responding to this question, if possible.

For example, one

consumer complaint I filed with the California Office of Attorney

General applies directly to case law,

3.3 Credit Scoring,

which is justified on “contractual necessity” only if it relies on

relevant information.

I was denied access to

my business banking account due to their use of an identity provider

which is a credit rating agency exempt from the CCPA,

is a registered data

broker, and also has a history of data breaches involving my compromised

answers to security questions pertaining to another individual

which I have no right to

correct.

In my case there was no

automated decisionmaking using machine-learning or artificial

intelligence algorithms:

just me and my US

passport standing in front of the bank branch manager who opened my

account but could not authenticate me for online-banking

because of a simple

“automated process” consisting of a flawed lookup table maintained by an

untrustworthy identity provider exempt from the CCPA.

Closing Comment

I want to thank the CPPA

for providing this opportunity to participate in its rulemaking process

through these public comments.

For brevity’s sake, my

Appendices are attached (if possible) to this submission,

and published in my

PrivacyPortfolio for peer review and collaboration with my professional

colleagues.

Like laws and audits, my own assumptions and proposals need to be tested.

Therefore, as a

follow-up to this public comment I will be conducting these tests on my

personal vendors

and sending my findings

to my vendors and the appropriate enforcement agencies and publishing

the results of my experiment in my public data catalog.

As a California Consumer

who exercises my own rights, I hope that the CPPA succeeds in providing

independent assurance to all stakeholders that critical assets and

citizen data are protected,

which is the stated goal

of Mandatory Independent Security Assessments of California Agencies.

Sincerely,

Craig Erickson, a California Consumer

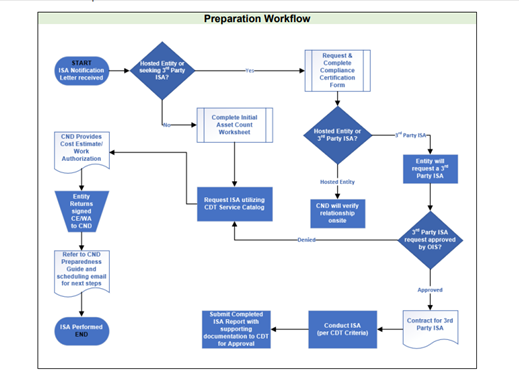

Use this as a process model for CCPA cybersecurity audits, based on output from CCPA risk assessments:

-

Entities begin the

ISA process when they receive a formal notification letter from

California Department of Technology (CDT)

Office of

Information Security (OIS) advising them that it is their year to

undergo an ISA.

a. Entities can seek approval to undergo a commercial, 3rd party ISA by attaching a copy of the proposed Statement of Work for the contract to the ISA Compliance Certification Form.

The completed ISA report must meet the ISA Criteria* EXACTLY and follow the SAME FORMAT.Note: All businesses and organization registered with the California Secretary of State should receive a “Welcome Packet” promoting awareness of the new CCPA Regulations and Resource Guide to help them comply with the Regulations and additional reporting requirements.

Note: Businesses and Consumers could use an online service to determine which classification status applies to the entity as

1) CCPA-Exempt; 2) CCPA-Covered; 3) Data Brokers; 4) Large Businesses; 5) High-Risk Processors.

This tool would also inform the user as to which obligations apply to each entity class.

For a CCPA-Exempt entity, it would state the entity has no legal obligations under the CCPA, and advise that a consumer may reasonably expect them to comply with the CCPA unless told otherwise.Note: All CCPA-covered entities should complete a Risk Assessment Questionnaire. This is designed to confirm or address any discrepancies in their classification status and assess their awareness of the CCPA through simple tests anyone could conduct.

For example, all CCPA-covered entities must have a published privacy policy, but if the policy predates the passage of the new CPRA-amended CCPA Regulations, it’s more likely than not that they are non-compliant and could recommend they consult the Resource Guide included in their "Welcome Packet".Note: All CCPA-covered entities classified as Data Brokers, Businesses Collecting Large Amounts of Personal Information, and High-Risk Processors would be required to fill out an Initial Asset Count Worksheet. This worksheet is designed to identify assets critical to the scope of an audit. It includes registered domains, websites, IoT devices, brand names, subsidiaries, parent companies. It would also include estimated counts of employees, consumer profiles, service providers, contractors, and third parties involved in collecting or processing PI. Counting the average number of sensitive data elements and attributes stored or processed helps the Agency designate which entities meet the criteria for mandatory risk assessments and audits.

Note: Audits and assessments are verified through testing controls, and the controls which are tested must be sampled from a finite population. Without making the entire inventory of system asset public information, input from consumers and other agencies can use other sources to verify or refute the scope of assets tested.

-

Entities begin the

ISA scheduling process by completing the Initial Asset Count Worksheet.

Note: The most significant difference between a CCPA risk assessment and a CCPA cybersecurity audit is that an audit's scope must be established using an inventory of assets, which would be, in my opinion, too burdensome on businesses submitting risk assessments.

Note: Unlike state agencies, expecting an inventory of assets for large or complex business entities, might be too burdensome on the Agency resources to verify accuracy and completeness.

-

Create the ISA Case

from the California Department of Technology (CDT) IT Services Portal

catalog

within 30 days of

the date of official notification.

-

Receive Confirmation

of ISA Dates and Cost Estimate/Work Authorization and return the signed

CE/WA to

the Cyber Network

Defense (CND) Engagement Manager who officially schedules the entity’s

assessment dates.

-

Entity receives a

copy of the CND Preparedness Guide from the CND Engagement Manager with

an email

confirming the

schedule for their ISA. The Preparedness Guide will enable the entity to

be as prepared

as possible for

CND’s arrival on site and to ensure the best possible outcome and

benefits from the ISA.

-

The ISA is conducted using a two-team approach.

The Risk Analysis (RA) team conducts (BLUE TEAM) tasks related to the defensive controls assessed (task sections 10-15).

The Penetration Test (Pen Test) team conducts (RED TEAM) activities related to the offensive simulation operations portion of the assessment (task sections 16-17).

If the Pen Test Team detects a Significant Risk, it will initiate a “Hard Pause” if delayed disclosure is likely to result in network compromise by a real-world threat actor. The Pen Test Team provides the Entity Liason with information pertaining to the detected risk, impacted host(s), and recommended course of action to reduce the risk to the enterprise.

If the CND detects the potential presence of Illegal Activity (external threat actor compromise, insider threat activities, etc.) the ISA will initiate a “Hard Stop”. The Pen Test Team, working with the entity’s management team, perform the required initial reporting to Cal-CSIRS as well as facilitate any interim evidence preservation process for red team actions.

Areas within the current ISA include host vulnerability assessments, firewall analysis, host hardening analysis, phishing susceptibility, network penetration testing, and snap-shot analysis of network traffic for signs of threat actor compromise.Note: This proposal is not suggesting that California Military Department (CMD) conducts all risk assessments, but that standards and guidelines for third-party assessors be aligned with CMD standards to a reasonable degree.

Proposal

The benefits to the CPPA

and OAG by leveraging existing policies, programs, procedures, and

resources within California State agencies

that align with intended

objectives of mandated cybersecurity audits and risk assessments

include:

- Reducing the cost/effort of auditors and auditees required to comply with legal mandates.

- The harmonization of laws and regulations at an inter-state and federal level based on established standards for cybersecurity.

-

Independent

verification and validation of cybersecurity audits and risk

assessments.

Note: Other significant laws relevant to the CCPA can also leverage this audit, assessment, and reporting process to help supplement and verify findings of non-compliance and high-risk activities.

| Bill | Subject | Latest Bill Version | Lead Authors | Status | Last History Action |

| AB 254 | Confidentiality of Medical Information Act: reproductive or sexual health application information | Introduced 1/19/2023 | Bauer-Kahan | Active Bill – In Committee Process | 2/2/2023 – Referred to Assembly Health Committee and Privacy and Consumer Protection Committee |

| AB-327 | Existing law establishes the California Cybersecurity Integration Center (Cal-CSIC) within the Office of Emergency Services, the primary mission of which is to reduce the likelihood and severity of cyber incidents that could damage California’s economy, its critical infrastructure, or computer networks in the state. | ||||

| AB 362 | Data brokers: registration | Introduced 2/8/2023 | Becker | ||

| AB 386 | California Right to Financial Privacy Act | Introduced 2/2/2023 | Nguyen | ||

| AB 677 | Confidentiality of Medical Information Act | Introduced 2/13/2023 | Addis | 4/14/2021, now relates to COVID-19 vaccination status and prohibitions on disclosure. covid vaccinations | |

| AB-694 | 1798.140. Definitions | 10/5/2021 – Approved by the Governor. Chaptered by Secretary of State – Chapter 525, Statutes of 2021. | |||

| AB 707 | Information Practices Act of 1977: commercial purposes | Introduced 2/13/2023 | Patterson | ||

| AB-1712 | Personal information: data breaches. | Irwin | Active Bill – Pending Referral | ||

| AB 726 | Information Practices Act of 1977: definitions | Introduced 2/13/2023 | Patterson | Active Bill – Pending Referral | 2/14/2023 – From printer. May be heard in committee March 16. |

| AB 733 | Invasion of privacy | Introduced 2/2/2023 | Fong, Hart | Active Bill – Pending Referral | 2/14/2023 – From printer. May be heard in committee March 16 |

| AB-749 | State agencies: information security: uniform standards. | Irwin | Active Bill - In Committee Process | ||

| AB 793 | Privacy: reverse demands | Introduced 2/13/2023 | Bonta | Active Bill – Pending Referral | 2/15/2023 – From printer. May be heard in committee March 16. |

| AB 801 | Student privacy: online personal information | Introduced 2/13/2023 | Patterson | Active Bill – Pending Referral | 2/14/2023 – From printer. May be heard in committee March 16. |

| AB-825 | Personal information: data breaches: genetic data. | Levine | 10/5/2021 – Approved by the Governor. Chaptered by Secretary of State – Chapter 527, Statutes of 2021. | ||

| AB 947 | California Consumer Privacy Act of 2018: Amends the law to require all five members of the California Privacy Protection Agency’s governing board to have qualifications, experience and skills in consumer rights, in addition to those in privacy, technology and other currently required areas. | CPPA Introduced 2/14/2023 | Gabriel | Active Bill – Pending Referral | 2/15/2023 – From printer. May be heard in committee March 17. |

| AB 1034 | Biometric information: law enforcement: surveillance | Introduced 2/15/2023 | Wilson | Active Bill – Pending Referral | 2/14/2023 – From printer. May be heard in committee March 18. |

| AB 1102 | Telecommunications: privacy protections: 988 calls | Introduced 2/15/2023 | Patterson | Active Bill – Pending Referral | 2/14/2023 – From printer. May be heard in committee March 18 |

| AB 1194 | California Privacy Rights Act of 2020: exemptions: abortion services | Introduced 2/16/2023 | Carrillo | Active Bill – Pending Referral | 2/16/2023 – Read first time. To print. |

| AB-1194 | California Privacy Rights Act of 2020: exemptions: abortion services. | Carrillo | Active Bill – Pending Referral | ||

| AB-1352 | Independent information security assessments: Military Department: local educational agencies. | Chau | |||

| AB 1394 | Commercial sexual exploitation: civil actions | Introduced 2/17/2023 | Wicks | Active Bill – Pending Referral | 2/18/2023 – From printer. May be heard in committee March 20 |

| AB 1463 | Information Practices Act of 1977 | Introduced 2/17/2023 | Lowenthal | Active Bill – Pending Referral | 2/17/2023 – Read first time. To print. |

| AB 1546 | California Consumer Privacy Act of 2018: statute of limitations | Introduced 2/17/2023 | Gabriel | Active Bill – Pending Referral | 2/17/2023 – Read first time. To print. |

| AB 1552 | Student privacy: online personal information | Introduced 2/17/2023 | Reyes | Active Bill – Pending Referral | 2/17/2023 – Read first time. To print. |

| AB 1552 | Student privacy: online personal information | Introduced 2/17/2023 | Reyes | Active Bill – Pending Referral | 2/18/2023 – From printer. May be heard in committee March 20 |

| AB-1651 | Labor statistics: annual report. Worker rights: Workplace Technology Accountability Act. | Kalra | Inactive bill – Died | 11/30/2022 – From committee without further action. | |

| AB-1711 | An act to amend Section 1798.29 of the Civil Code, relating to Privacy: breach | Seyarto | |||

| AB 1712 | Personal information: data breaches | Introduced 2/17/2023 | Irwin | Active Bill – Pending Referral | 2/18/2023 – From printer. May be heard in committee March 20 |

| AB 1721 | California Consumer Privacy Act of 2018 | Introduced 2/16/2023 | Ta | Active Bill – Pending Referral | 2/17/2023 – Read first time. To print. |

| AB-2089 | Privacy: mental health digital services: mental health application information. | Bauer-Kahan. | |||

| AB-2355 | School cybersecurity. | Salas | |||

| AB-2958 | Committee on Judiciary. State Bar of California. | ||||

| SB-41 | Privacy: genetic testing companies. | Umberg | |||

| SB 287 | Features that harm child users: civil penalty | Introduced 2/2/2023 | Skinner | Active Bill – In Committee Process | 2/15/2023 – Referred to Senate Judiciary Committee and Appropriations Committee |

| SB 296 | In-vehicle cameras | Introduced 2/2/2023 | Dodd | Active Bill – In Committee Process | 2/15/2023 – Referred to Senate Judiciary Committee. |

| SB 611 | Information Practices Act of 1977 | Introduced 2/15/2023 | Menjivar | Active Bill – Pending Referral | 2/16/2023 – From printer. May be heard in committee March 18. |

| SB 793 | Insurance: privacy notices and personal information Introduced 2/16/2023 | Glazer | Active Bill – Pending Referral | 2/17/2023 – Read first time. To Senate Rules Committee for assignment. To print. | |

| SB 845 | Let Parents Choose Protection Act of 2023 | Introduced 2/17/2023 | Stern | Active Bill – Pending Referral | 2/21/2023 – From printer. May be heard in committee March 20 |

| SB 875 | Referral source for residential care facilities for the elderly: duties | Introduced 2/17/2023 | Glazer | Active Bill – Pending Referral | 2/17/2023 – Read first time. To Senate Rules Committee for assignment. To print. |

| SB-1059 | Privacy: data brokers. | Becker. | Inactive bill – Died | 11/30/2022 – From committee without further action | |

| SB-1140 | Public social services: electronic benefits transfer cards. | Umberg. | |||

| SB-1454 | California Privacy Rights Act of 2020: exemptions. | Archuleta. | Inactive bill – Died | 11/30/2022 – From committee without further action. |

Proposal

Use this smaller subset

of common controls from NIST, ISO, CIS, and OWASP to establish a minimum

standard nearly all businesses can meet.

If more stringent

standards are needed due to significantly greater risk exposure or harm,

they can be layered on top of the baseline,

much like PCI-DSS or

HITRUST is structured.

This control subset is

documented in this Excel Workbook, published in my public data catalog

accessible from this link:

Appendix C - NIST Control Standards for CCPA Risk Assessments.xlsx

Note: The methodology I used to create a smaller subset was:

- select the greatest number of common controls from all standards

- select the controls most relevant to CCPA test cases and mandated cybersecurity audits and assessments.

- select controls that can be most easily tested and verified by other businesses and consumers.

Note: NIST 800-53r4 is

the current standard for California Office Information Security.

This proposed control

set uses Revision 5 which incorporates many controls from the Privacy

Framework and Cybersecurity Framework for Improving Critical

Infrastructure.

It represents a baseline

canonical model, which all other standard control frameworks are mapped

to.

National Institute

of Standards and Technology Special Publication 800-53, Revision 5

This publication

provides a catalog of security and privacy controls for information

systems and organizations

to protect

organizational operations and assets, individuals, other organizations,

and the Nation from a

diverse set of threats and risks, including hostile attacks,

human errors, natural

disasters, structural failures, foreign intelligence entities, and

privacy risks.

The controls are

flexible and customizable and implemented as part of an

organization-wide process to manage risk.

The controls address

diverse requirements derived from mission and business needs, laws,

executive orders,

directives, regulations,

policies, standards, and guidelines.

Finally, the

consolidated control catalog addresses security and privacy from a

functionality perspective

(i.e., the strength of

functions and mechanisms provided by the controls) and from an assurance

perspective

(i.e., the measure of

confidence in the security or privacy capability provided by the

controls).

Addressing functionality

and assurance

helps to ensure that

information technology products and the systems that rely on those

products are sufficiently trustworthy.